We already know food labels work. Is it time for compulsory carbon labelling?

Pushing brands to show the climate footprint of their products is in many ways the final frontier of food labelling. What can we learn from previous policy success?

Think about the last time you went to the supermarket. It probably didn’t occur to you, as you picked out the pasta shape and jarred sauce that was calling out to you most in that particular moment, but you weren’t in a neutral space.

In fact, from the structure of the strip-lit aisles to the small print on the back of each identical tin of beans, every inch and element had been designed with your behaviour – and that of other consumers – in mind.

From placing premium products at eye-level to fluorescent buy-one-get-one-free stickers, some of this is about encouraging spending. Some, however, relates to encouraging healthy choices. Jostling for space next to those BOGOF stickers are legally-required food labels; companies need to display the ingredients, nutritional and allergen information of their products loud – whether or not they’re proud.

It wasn’t always like that. The nutrition information panel first appeared over 20 years ago, adopted voluntarily – due to consumer demand – and then by law. At first, there was a huge amount of confusion; people didn’t understand the numbers and graphs, how they compared to each other, or how to translate them into balanced dinners and longer lives. There was also industry commotion; labels became ‘battlegrounds’, with one scheme eliciting ‘bouquets and brickbats’.

Nowadays, however, 80% of shoppers say they often look at nutritional information when choosing what to buy. And data confirms that, rather than offering the luxury of choice alone, labels incentivise healthy behaviours. Meta-analysis has found that labels reduce calorie intake by around 6.6%, total fat by 10.6%, and other generally unhealthy choices by 13% – and increase vegetable intake by 13.5%.

And how about when you get to the end of your supermarket sojourn? Do you need a bag for your pasta and sauce? Probably not. When the 5p (now 10p) plastic bag charge was first introduced in 2015, most people wondered what the point was. ‘Plastic bag chaos looms: As 5p charge starts in England, shoppers face tangle of red tape’, ran the front page of the Daily Mail. Fast-forward to now, and plastic bag use has fallen by 95%.

This leads us to a final frontier, relevant not just to our bodies and our bins, but to the health of the planet. “Why should nutritional impact be labelled any differently to the impact on our planet?” asks Ellie Colenso, Head of Community at Tenzing, which earlier this year became the first soft drink in the world to implement climate footprint labelling.

“20 years ago, people did not understand calories or what those numbers meant, but now our purchases are guided by these numbers. This is what we believe carbon labelling will become too, but we need it to take far less time than calories did!”

Carbon ‘foodprinting’: what it means for consumers and brands

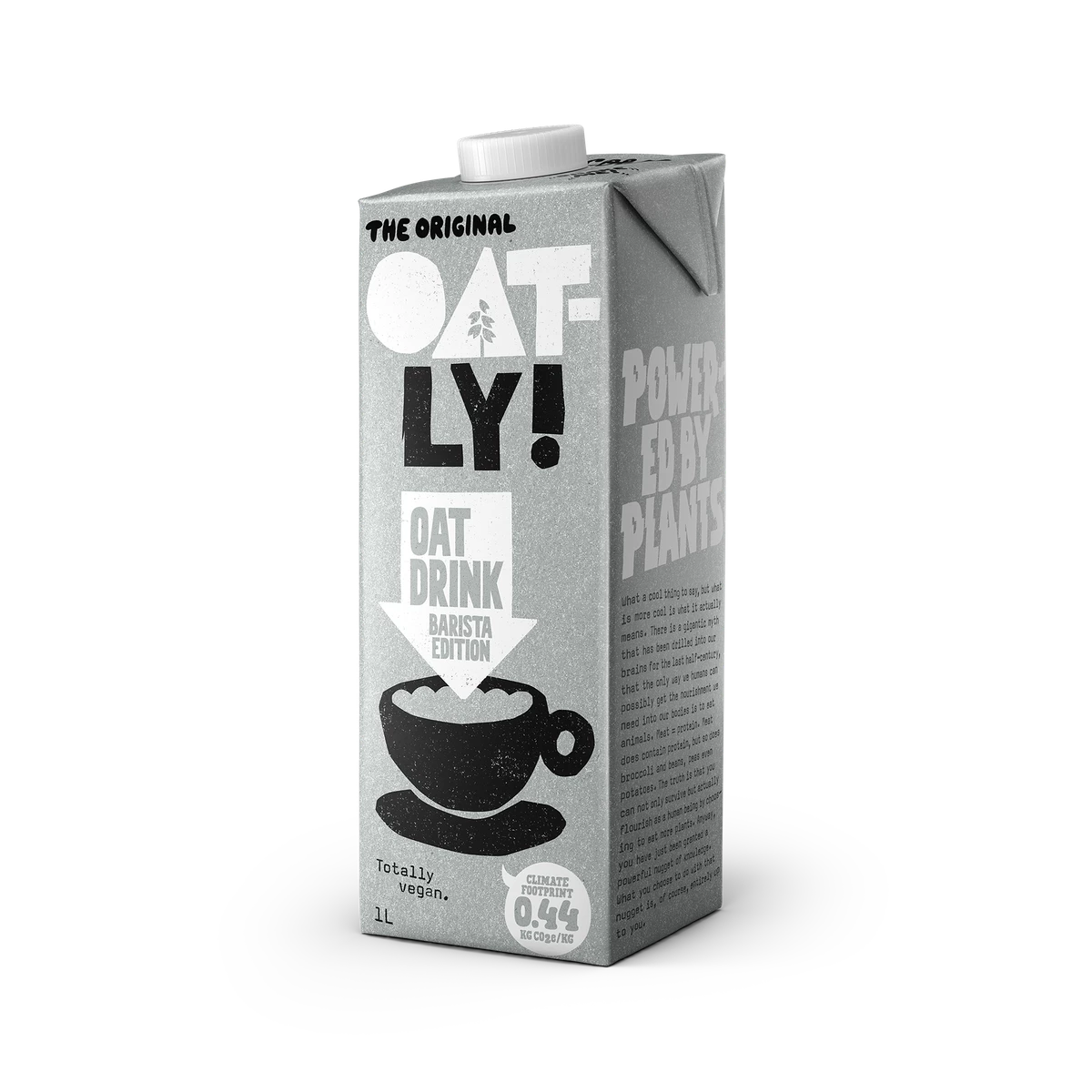

Carbon labelling involves quantifying the (kilo)grams of carbon dioxide released due to the production of each specific product. For example: the climate footprint of Oatly Barista Edition is, according to the brand itself, 0.44kg of CO2 per kg.

From the slim amount of information available it looks like, as with food labelling, showing climate impact influences consumer behaviour. One study from earlier this year suggests that those who wanted to know carbon information reduced their emissions by 32% on seeing it. Interestingly, even those who didn’t want to know made choices that were 12% greener.

But – crucially – carbon labelling is about more than just consumer behaviour change. It may well have its most meaningful impact on brands, directly.

There are precedents for this in the world of food too. In 2006, US legislators forced companies to disclose the amount of trans fatty acids in their products. These companies then altered their recipes to essentially get rid of trans fats. As Sean Cash, from the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, told Positive News,

“We got most of the way towards a removal of trans fats from the processed food supply in the US just through a requirement of disclosure. It was almost as good as a ban.”

Likewise, labelling precipitates an awareness of and transparency about what goes on in specific supply chains. This, in turn, can form the backbone of more involved policy.

“Labelling alone will not solve our problems,” Anya Doherty, CEO and founder of Foodsteps, a platform that partners with food businesses to track carbon impact from farm to fork, tells Ours to Save.

“We have had nutritional labelling for decades and still have a health crisis related to diet. Carbon labelling is likely to produce the same outcome; it won’t be a silver bullet solution. However, nutritional labelling has allowed policies like the Sugar Tax to come in, since all companies were reporting using standardised metrics. Carbon labelling could allow for policies like this.”

The Soft Drinks Industry Levy (AKA the Sugar Tax) came into force in 2018, many focused on the effect that price rises – incorporating the 24p/litre tax imposed on drinks with more than 8g sugar/100ml – would have on consumer choices. Would people buy less soft drinks because of this price hike?

Recent research from the BMJ suggests that no, people aren’t buying fewer drinks. However, they are consuming less sugar from soft drinks. This was because the prime impact of the sugar tax was actually recipe reformulation. Around 50% of UK manufacturers cut sugar preemptively to avoid paying the top tax rate.

Towards supply chain transparency and a green food system

It’s not inconceivable that compulsory carbon labelling would elicit similar reform in top offenders. Greenwashing doesn’t work so well when you have an all-revealing number slapped front and centre on your product. And those who have not seen fit to mention – or even think about – the climate impact of their produce may suddenly be spurred into action, if they have to report on it. Embarrassment is a powerful thing.

Although a law on carbon labelling remains a while off, several brands are leading the charge by self-reporting their footprints. As Doherty says, “The more companies that carbon label their items, through various schemes, the greater the ‘threat’ of across-the-board legislation and standardisation.”

Thanks to Foundation Earth, front-of-pack environmental scores are being piloted on hundreds of products across Lidl, Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Aldi, Morrisons and M&S.

And leading the charge for smaller businesses is the #Knowvember pop-up store, based on Rivington Street in Shoreditch until close of play on this Saturday 6th. It’s the world’s first climate transparent store, only stocking brands that know and display their carbon footprint.

For these brands and others like them, instigating a thorough audit has provided the opportunity to make changes for the better. Doherty sums it up: “For some of our larger clients, labelling items in large product ranges – with both high and low impacts – has created clear incentives to shift towards producing lower-impact food.” And this is with an internal audit alone.

Colenso from Tenzing, which is taking part in #Knowvember, says that “By understanding our carbon footprint in more detail, we were able to identify the largest carbon contributors in our supply chain and make changes accordingly.”

“We switched our production from The Netherlands to the UK, for example, to reduce our transportation emissions post-production.”

Another participating brand, Little Freddie, is “now working on alternative routes and modes of transport to reduce our carbon emissions… for example using multi-modal transport (rail, road and sea) as opposed to just road.”

Ombar has “built an environmental commitment into the job descriptions of the entire team, no matter their role, so that all of us are committed to finding ways to make a difference”. And Rubies in the Rubble is offering “ceramically printed glass bottles that customers can fill with ketchup, and then pop in the wash to be reused again and again.”

Whether by foregrounding the good guys, or stirring the main offenders into action, data suggests something as small as a label can make a difference. But – as we can see from previous food policy – labels mean little until a universal standard exists and is enforced, meaning one brand can be compared to another. Thanks to forward-thinking businesses and vocal customers, cultural pressure is mounting – but change can’t come soon enough.

This article was published as part of a paid partnership with Tenzing, raising awareness of the #Knowvember campaign. Learn more here and visit the pop-up store at 73 Rivington Street, Shoreditch until close of play on Saturday 6th November.